This is my second article round up. The first is over at my old blog here. In this post, I’ll briefly cover two Atlantic articles related to economic inequality and the differing economic expectations of democrats and republicans. Most time is spent reviewing a new working paper on the correlation between Trump’s twitter activity and hate crimes, and thinking about how it could make the jump from correlation to causation.

Income Inequality

Matthew Stuart’s “The 9.9 Percent Is the New American Aristocracy” and Jordan Weissman’s reply “Actually, the 1 Percent Are Still the Problem”

The first article is quite long, but easily skim-able. It focuses on not the super wealthy but the elite professionals that make up the upper class and the pernicious ways that group has convinced itself that membership is meritocratic when in reality parental wealth is inherited to a high degree. The various mechanism for this inheritance are in the article (knowing what preschools to go to, what SAT tutors to hire, etc.), but it also pointed out that this group (to which I belong) often refuses to acknowledge that they are upper class and do not represent the “average American.” And that self-delusion of meritocracy can be quite dangerous when it is used to justify the status quo.

Weissman’s response makes the valid point that the top 90th percentile to the 99.9th percentile of the income distribution are quite heterogeneous: the elite professionals are in there but also are old retirees. And he points out that the difference in wealth and privilege between the 90th and 99th percentiles is quite large. Therefore, the 9.9% are not even a cohesive group, let alone “the New American Aristocracy.” Often when reading about a subject I’m not personally knowledgeable on, I find myself agreeing with whoever I’m reading. This Slate article pushed back on the data and factual claims in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to do myself just assessing the analytical arguments.

Partisan Economies

Annie Lowrey’s “Left Economy, Right Economy”

An interesting look into how the partisan change in post-election economic expectations hasn’t disappeared after 2016. The article goes into how democrats and republicans have radically different economic expectations. This is one of the more easily measured areas of where partisan beliefs can impact non-political opinions. They also cite some good research that “politically-motivated” beliefs about the direction of the economy don’t impact consumer spending, indicating that perhaps the people espousing the motivated beliefs know that they are untrue.

On some level, this shouldn’t be surprising. Democrats and republicans disagree on the empirical question of which policies improve the economy. On the other hand, to the extent that economies aren’t that impacted by government policies, it is a huge collection of people looking at the same data and coming to opposite conclusions.

Trump Tweets and Hate Crimes

Karsten Müller and Carlo Schwarz’s “Making America Hate Again? Twitter and Hate Crime Under Trump”

A lot has been written about whether the 2016 election and Trump’s campaign emboldened racists. A new working paper from economists at the University of Warwick took a look at whether Trumps activity on Twitter is related to an increase in hate crimes. The abstract is below.

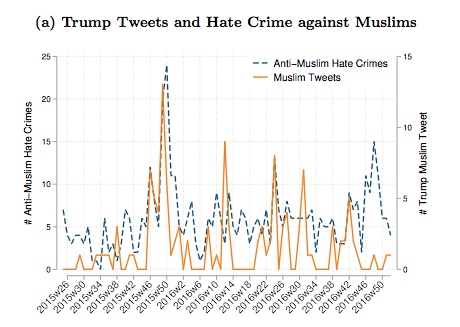

This is the main figure:Abstract: Social media has come under increasing scrutiny for reinforcing people’s pre-existing viewpoints which, it is argued, can create information “echo chambers.” We investigate whether social media motivates real-life action, with a focus on hate crimes in the United States. We show that the rise in anti-Muslim hate crimes since Donald Trump’s presidential campaign has been concentrated in counties with high Twitter usage. Consistent with a role for social media, Trump’s Tweets on Islam-related topics are highly correlated with anti-Muslim hate crime after, but not before the start of his presidential campaign, and are uncorrelated with other types of hate crimes. These patterns stand out in historical comparison: counties with many Twitter users today did not consistently experience more anti-Muslim hate crimes during previous presidencies.

Islam-related tweets and the number of anti-Muslim hate crimes

in the US after the start of Trump’s presidential campaign.

Some other key results:

“Trump’s Muslim tweets alone predict more than 20% of the variation in anti-Muslim hate crimes in the same week, but only after his campaign start; the explanatory power is less than 1% before.”

“[T]he number of hate crimes [in counties with low and high twitter usage] was more or less constant since 2009. With the start of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign on June, 16th 2015, however, we observe a disproportional increase in the number of hate crimes in those counties where many people use Twitter. There is no comparable increase in counties with low twitter usage.”

“In additional exercises, reported in Supplementary Material 6, we find complementary results for Hispanics. While the association weakens somewhat in the immediate run-up to the election in mid-2016, Table A.10 and Table A.11 show that Trump’s tweets about Hispanics have considerable predictive power for Ethnicity-based hate crimes. Again, this only holds true for the period after his campaign start, and not for other types of crime biases.”

The correlation is quite striking. It kind of makes me wish that the Twitter employee who deleted Trump’s account on their last day would come back to quit every day (or at least pick random days to delete the account).

I thought this paper was really interesting for a couple of reasons. Foremost, it gets about as close as possible to claiming and showing that a correlation is causal. They do many, many robustness checks that, while imperfect, all indicate that alternative explanations are unlikely. Of course, correlation does not imply causation in the mathematical sense, but it does imply it in the colloquial sense. If Trump’s anti-Muslim tweets are in response to world events that would cause an increase in hate crimes absent his tweets, you would expect a similar correlation between his tweets and hate crimes before his presidential run. But that correlation isn’t observed. If high twitter usage counties are more prone to hate crimes, you would expect elevated levels of hate crimes before he became president. But that correlation also isn’t observed. Other counter arguments to the (unstated) causal claim are similarly addressed.

If the paper did try to make a causal claim (which it does not), the appropriate counter-factual is an interesting discussion. The counter-factual of anti-Muslim hate crimes under a Clinton presidency is the most relevant for a judgement on Trump’s presidency, but hard to estimate. The counter-factual of Trump wants to send an anti-Muslim tweet but does not or cannot for some reason is less relevant, but much easier to estimate. Some ways to get at this counter-factual would be to identify times when Trump was not able to tweet. I’m not sure if he gets service on Air Force One, but time spent traveling or in meetings could be used as an instrument for his Islam-related tweets. Unfortunately, the time periods he is otherwise occupied with presidential work are probably too short and infrequent. Long periods while he is overseas, he might tweet at odd hours, so the exposure of Twitter to his tweets could be plausibly thought of as exogenously lowered. Essentially these methods try to find “random” reasons that Twitter was more or less less exposed to Trump, then use the variation in Trump’s Islam-related tweets attributable to those random shocks to explain variation in hate crimes. That final explanation is causal because the ultimate source of the variation is random.

Another way to get at the counter-factual is to try to identify “random” tweets, i.e. anti-Muslim tweets not caused by other events. This kind of analysis has been explored in finance when doing event studies of how unexpected news affects a company’s stock price. Reviews of each of his at-issue tweets and a selection of events that could cause an increase in anti-Muslim hate crimes could identify events and tweets that are linked (such as the travel ban and resulting tweets), events that were not tweeted, and tweets not associated with events. The PredictIt markets for the number of tweets he sends each week could even be used to create “expected” levels of Twitter activity, then deviations from that expectation could be treated as unexpected shocks. Of course, that relies on the strong assumption that PredictIt Twitter markets are efficient. Choosing the events to analyze would be hard too, but you could potentially algorithmically identify events that sparked many tweets related to Islam in the US and select from those.

This last method gets at what I think is probably the true causal structure. Trump’s election and campaign emboldened people who harbored racial resentment and increased the baseline rate of hate crimes. Trump’s tweets are caused by news-worthy events that would have received coverage on traditional and social media. Those events and the coverage would have caused an increase in hate crimes regardless of his tweets. When he does choose to tweet about them, he increases their exposure and amplifies their impact on anti-Muslim hate crimes. Separating events and tweets into three categories (event-tweet pairs, unpaired events, and unpaired tweets) and comparing before and after Trump’s campaign began can fully test at least the correlations implied by this theory. To the degree that the pairing and non-pairing of tweets and events is exogenous, the correlations become causal as well. That exogeneity isn’t something that can be statistically tested but can come from a qualitative analysis of the time surrounding the event and/or tweet.

The paper is going through the peer review process, so what comes out the other side may be quite different. It does a lot of interesting analysis and adds to an important discussion about the consequences of the 2016 election. I certainly do not expect this to be the last paper on the impact of Trump on racial resentment in America.